There is a moment when color reveals itself as more than pigment — when a child stirs two shades together and pauses, watching one hue surrender into another. The magic is quiet but transformative. It is not simply about “mixing colors” but discovering new ways of being, expressing, and remembering. In that soft unfolding, color becomes a language, a medium of emotion and reflection — one that asks us, as educators, to chronicle what children are becoming through hue.

In our mixed-age atelier, color lives in jars, pastels, watercolor trays, and loose powders — but mostly, it lives in the stories that children tell through their choices. A two-year-old’s broad stroke of red becomes an exclamation of presence, while a five-year-old returns to the same red weeks later, softening it with white and calling it “the sky before it rains.” To chronicle these moments is to notice not just what colors were used, but what they meant in that moment of becoming.

Beyond Documentation

Documentation can capture what happened — the materials offered, the sequence of events, the finished image — but chronicling asks us to dwell in the unfolding. It invites a pedagogy of listening, where we trace the evolution of thought through time. When we chronicle children’s engagement with color, we’re not compiling evidence of learning outcomes; we’re participating in a conversation that unfolds across days, weeks, and seasons.

As the same palette is revisited, the hues deepen in meaning. A child once fascinated by bold primary tones begins to linger in gradients — exploring the subtle shift between orange and coral. Another child, once hesitant to paint at all, begins tracing faint lines of lavender across the page, whispering that this one “feels quiet.” Through the act of revisiting, children come to see color not as a fixed category, but as alive, relational, and expressive.

Color as Emotional Geography

Color offers children a way to navigate feelings too vast for words. A palette becomes a map of memory and mood. During one morning in our studio, I watched a group of children gather around an easel covered in varying shades of blue. “This one is cold,” one child said. Another replied, “No, this one is sad.” A third added a streak of yellow across the canvas, declaring, “Now it’s getting better.”

Their dialogue revealed color as a shared emotional landscape — a way of narrating how the inner world meets the outer one. When we chronicle these exchanges, we begin to see how children use hue to construct meaning, to heal, to connect.

Revisiting Color as Revisiting Self

When children return to color, they return to a version of themselves that existed before — and to the new version that stands before it now. A child who once painted with exuberant, unblended reds may later approach the same pigment with intention and nuance. Revisiting offers a mirror — a way to encounter change without losing continuity.

In chronicling these revisitations, we, too, become witnesses to transformation. The red of early joy becomes the burgundy of quiet confidence; the green of discovery becomes the teal of reflection. Each reencounter with color is an opportunity for children to weave together past and present — to understand that growth is not replacement, but layering.

The Educator as Chronicler

To truly see color through the child’s eyes, the educator must slow down. Chronicling asks us to sit beside, to observe without interruption, to trace the rhythms of return. Instead of photographing the “final” painting, we listen to the conversations that rise between brushstrokes. We notice the gestures of thought: the tilt of the wrist as a child mixes water into pigment, the quiet hum that accompanies concentration, the choice to blend or to resist blending altogether.

These are the details that give life to the child’s thinking — and to our understanding of their relationship with materials, with self, and with one another. Chronicling color is about entering the process as co-researchers, not recorders.

Materials as Co-Participants

The materials themselves hold memory. The brushes stained from yesterday’s mixtures whisper of past explorations. The jars of water, now clouded with pigment, carry traces of collaborative inquiry. When we invite children to revisit these remnants, they discover continuity — that their previous work has left marks in the environment, just as their experiences have left marks within them.

Charcoal, oil pastels, and watercolor do not simply offer “variety”; they offer perspective. Each medium extends the child’s capacity to think with color, to experiment with opacity, transparency, and saturation as extensions of mood and metaphor.

The Language of Hue

Through chronicling, we begin to see that color has its own syntax — one that children instinctively understand long before formal instruction. Red can interrupt; blue can soothe; yellow can awaken. Children combine them not for harmony alone but for meaning.

A group of four-year-olds once created a collaborative canvas in our studio. At first, each worked independently, claiming corners with distinct palettes. But slowly, their colors began to meet — red brushing against blue, yellow drifting into green. “They’re friends now,” one child said. In that single remark, she articulated what color theory — and indeed, what human development — is about: connection through difference, understanding through relation.

Closing Reflection

When we chronicle children’s journeys with color, we learn to see hue as language, emotion, and identity all at once. Color theory becomes a living, breathing inquiry — not a curriculum to deliver, but a landscape to enter alongside the child. Revisiting allows both children and educators to see anew, to understand that meaning is not static but ever-unfolding.

As Wassily Kandinsky once wrote, “Color is a power which directly influences the soul.” It is through this power — this dialogue of hue and heart — that we come to know not only the children’s learning, but our own.

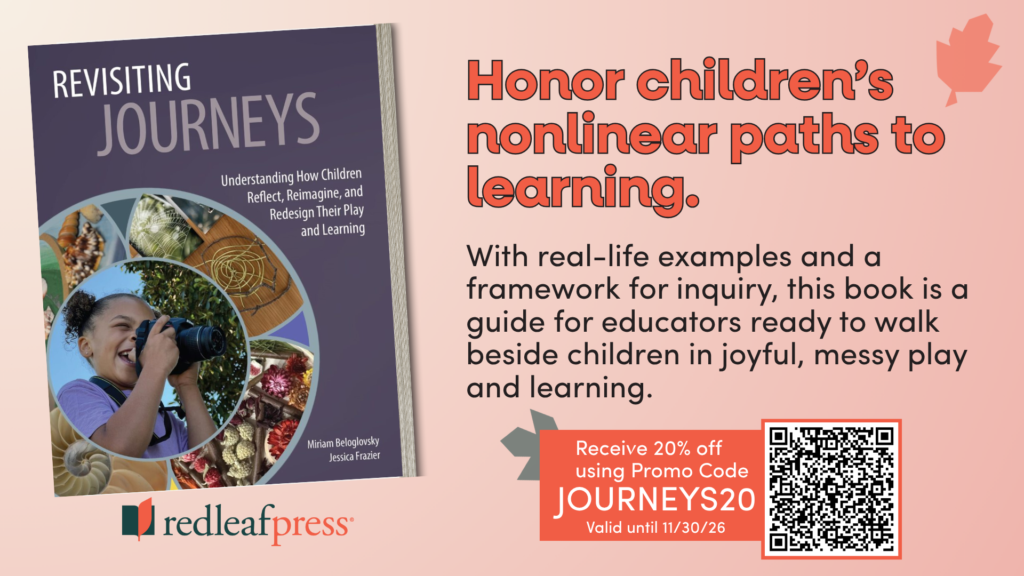

Read More

Preorder the Book you can get 20% discount until November 30 2025