The Story Beneath the Stories

Every early childhood classroom hums with stories — stories of invention, connection, and wonder. Children move through their days weaving ideas into play, constructing meaning through conversation, and revisiting discoveries in new ways.

But amid the joyful noise of daily life — the block towers, the paint and clay-covered hands, the spontaneous performances — the threads of those stories can sometimes slip past us.

As educators, we document. We take photos, write notes, record snippets of dialogue. Yet, often our documentation still tells the story from our point of view.

Chronicling invites something deeper.

What Is Chronicling?

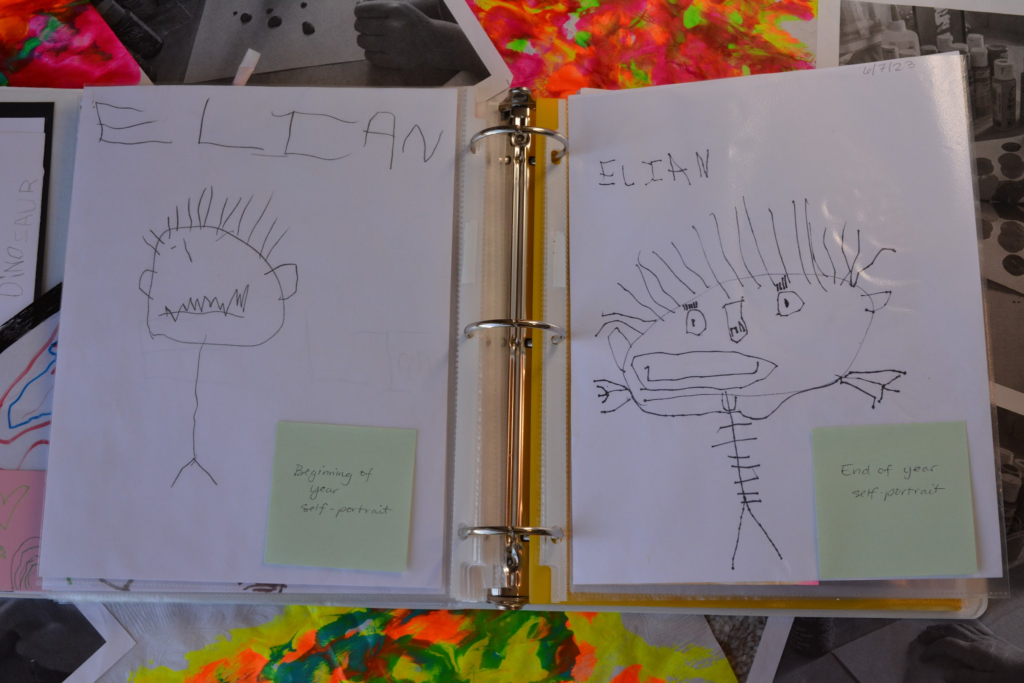

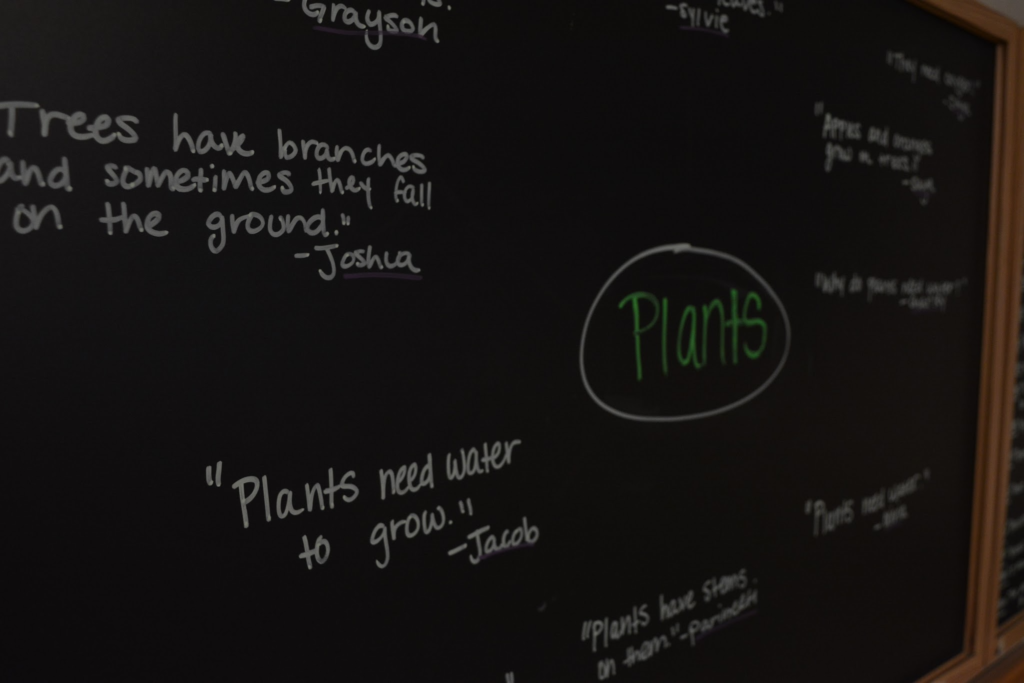

Chronicling is a reflective, collaborative approach to documentation that centers the child’s voice and perspective, as opposed to documentation that only takes into account the educator’s perspective.

It’s a way of co-authoring the children’s stories with them, rather than about them.

Instead of capturing learning as an artifact to look back on later, chronicling transforms the process into an ongoing, participatory dialogue. The emphasis shifts from what happened to how meaning is made and remade over time.

“What do children want to remember about their own discoveries?”

“What images, words, or experiences do they feel tell the story best?”

By asking these questions, chronicling opens up powerful opportunities for children to engage in metacognition — thinking about their thinking — and to see themselves as competent, reflective learners.

From Documentation to Co-Authorship

Traditional documentation often reflects the teacher’s lens: what we found interesting, what we interpreted as meaningful. Chronicling, however, shifts that stance toward shared authorship.

Imagine a group of children exploring shadows. Rather than simply photographing their play and adding your interpretation, you invite them into the documentation process:

- “Which photo shows the shadow you were most curious about?”

- “What would you like to tell others about this moment?”

- “How did you figure out what your shadow could do?”

When children help choose, describe, and revisit their moments of learning, they take ownership of their narrative. They begin to connect ideas across time — linking today’s discoveries to yesterday’s experiments.

The chronicle becomes a living story, evolving alongside their thinking.

The Classroom Ecosystem Chronicle: A Living Space of Reflection

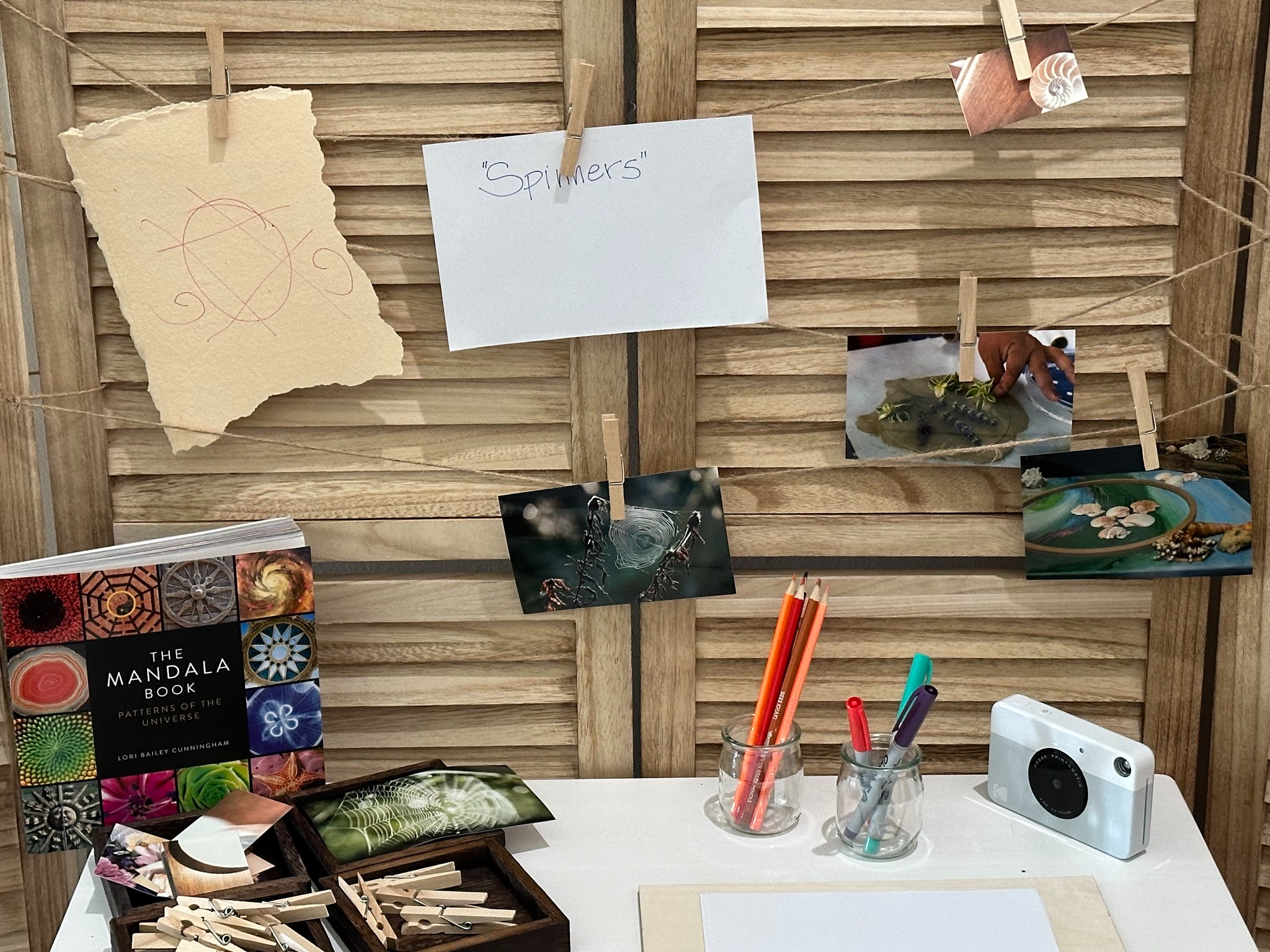

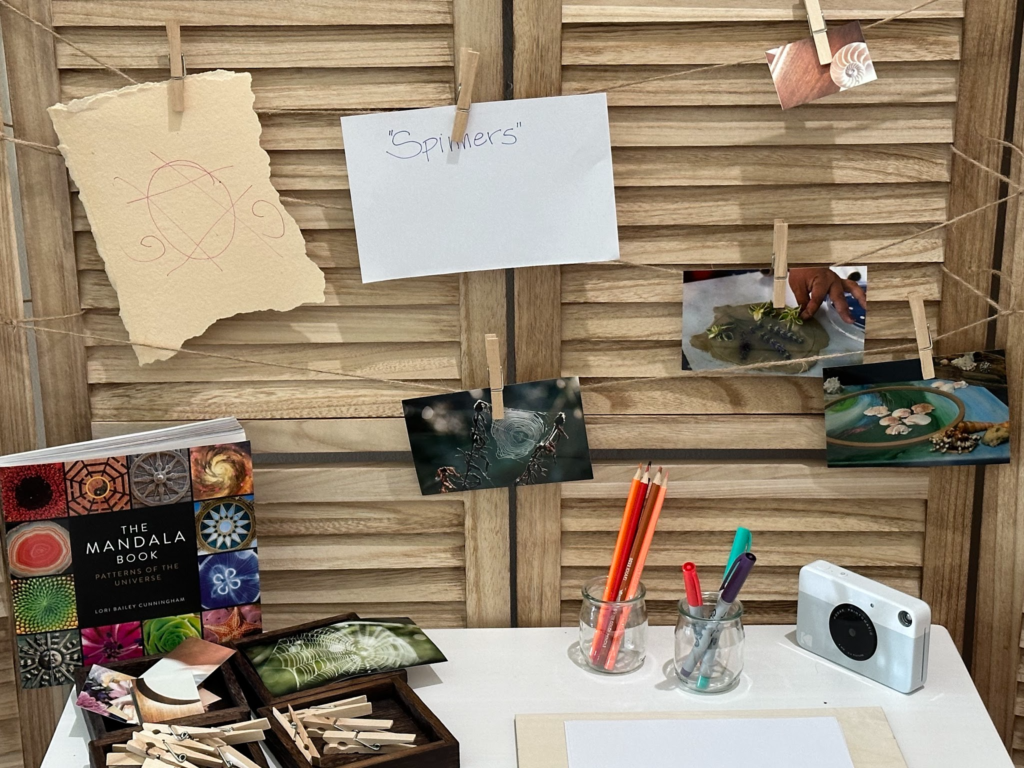

A classroom ecosystem chronicle can take many forms — a wall of images and notes, a shared journal, or even a table display where artifacts evolve over time.

What matters most is that it remains alive and accessible.

Children should be able to revisit it, rearrange it, add to it, and reflect on it.

In doing so, they begin to see their learning as a continuous thread rather than a series of disconnected events.

When children stand before the chronicle wall and say things like:

“That’s when we made the rainbow tunnel!”

“Remember when we thought the water would stop, but it kept going?”

—they are narrating not only what they did, but who they are as learners.

Through these revisiting moments, educators gain deeper insight into how children construct meaning. The chronicle becomes a dialogue between children’s evolving theories and our responsive teaching.

The Educator’s Chronicle: A Parallel Journey

Chronicling isn’t just about the children — it also documents the educator’s evolving understanding.

As we engage in chronicling, we begin to see patterns in our observations. We notice what captures children’s curiosity, where our scaffolding supports or constrains, and how our environments provoke thinking.

This reflective process transforms teaching into a cycle of inquiry:

- Observe and listen deeply.

- Chronicle collaboratively.

- Revisit and reflect with children.

- Plan and respond based on what emerges.

Through this rhythm, chronicling becomes both a pedagogical tool and a professional mirror. It helps us articulate the why behind our choices, making our intentionality visible to colleagues and families.

Chronicling as a Shared Narrative

When we share chronicles with families, something magical happens. Parents begin to see not just what their child did, but how they think, negotiate, wonder, and persevere.

The chronicle speaks to families in a language of process and growth rather than product or achievement. It invites them into the learning journey as active participants, capable of contributing new perspectives and insights.

Chronicling becomes a bridge — connecting school and home, child and teacher, reflection and action.

Why It Matters

Chronicling challenges us to reimagine the power dynamics of documentation.

It asks us to let go of being the sole narrator and instead become co-authors and co-researchers alongside children.

This shift reflects a deeply held belief of Reggio-inspired practice — that knowledge is constructed socially, through dialogue and shared meaning-making.

When children chronicle, they learn that their voices carry value and that reflection is part of learning, not just an afterthought.

When educators chronicle, we learn to listen with curiosity, to embrace uncertainty, and to honor the stories that unfold in ways we might never have planned.

Starting Small: Practical Invitations

If you’re curious to begin chronicling in your own setting, try starting small:

- Invite children to revisit photos or video clips and tell you what’s happening. Notice what they recall or emphasize.

- Create a shared space where children can post their own “important moments” — drawings, notes, photos, or artifacts.

- Use revisiting circles where you look back on previous explorations together and ask, “What did we learn from this?”

- Ask children to dictate or record their own captions for documentation panels.

- Keep your reflections visible, too — include your questions or insights alongside theirs.

Each small step builds toward a culture of co-authorship, where both children and educators are seen as learners in relationship.

A Living Practice

Ultimately, chronicling isn’t a product — it’s a practice.

It reminds us that documentation is not an endpoint but an evolving conversation about identity, meaning, and growth.

When we chronicle learning, we slow down.

We listen more closely.

We become witnesses not only to what children know, but to who they are becoming.

And perhaps most beautifully, we invite them to see themselves the same way — as authors of their own unfolding stories.

Reflection for Educators

As you consider chronicling in your own context, take a moment to reflect:

- How might chronicling shift the way you see your role as an educator?

- What would it look like for your documentation to include the children’s voices and choices?

- How might your classroom ecosystem change if children could see and revisit their own play and learning every day?

Closing Thought

Chronicling reminds us that teaching is not just about delivering content — it’s about creating shared narratives of becoming.

When we chronicle together, we are not simply recording what happened;

we are co-authoring what matters.

“When teachers are listening and responding, children become animated and involved.” — Loris Malaguzzi

May our listening continue to animate our classrooms — and may our chronicles tell the living stories of learning that grow within them.

Read the book: Revisiting Journeys: Understand How Children Reflect, Reimagine and Redesign Learning by Miriam Beloglovsky and Jessica Frazier. Published by Redleaf Press